[A version of the following blog was given as remarks made at a special expert session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body (INB) to draft and negotiate a WHO convention, agreement or other international instrument on pandemic prevention, preparedness and response]

The scrambling for access to Covid-19 vaccines by developing countries has reignited the debate on the WTO Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement and its effects on public health.

In such debates, the TRIPS Agreement is often cast as “the big evil”.

There is no denying that the TRIPS Agreement, adopted in 1995, ushered in intellectual property (IP) norms and standards derived from high-income countries that were ill-suited to the needs of developing nations.

Disputes over access to HIV medicines in the late nineties and early 2000s, and, more recently, over Covid-19 vaccines and therapeutics, may confirm the view that TRIPS does not serve the public interest well.

However, the stated objective of the TRIPS Agreement is oriented toward creating societal benefits for all.

It reads:

The protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights should contribute to the promotion of technological innovation and to the transfer and dissemination of technology, to the mutual advantage of producers and users of technological knowledge and in a manner conducive to social and economic welfare, and to a balance of rights and obligations.

Article 8 acknowledges countries’ rights to take measures to protect the public interest and specifically public health. It further states that measures may be needed to prevent abuse by IP holders and measures against practices that restrain trade or adversely affect technology transfer.

The Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health, adopted by the WTO Ministerial Conference in 2001 confirmed this right and spotlighted compulsory licensing as a means to ensure access to medicines for all.

A few words about compulsory and voluntary licensing

Our organisation maintains a database of the use of these TRIPS flexibilities for public health.

The data shows, since 2021, ten new compulsory licensing instances and all concerned products to prevent or treat Covid-19.

Research by Knowledge Ecology International, a non-profit think tank, has found 62 Covid-19 contracts by the US Government containing authorisation of non-voluntary use of third party patents. For example, Moderna is a beneficiary of such CLs, which enabled Moderna to develop their mRNA vaccines without concerns about patent infringement lawsuits.

Our data also shows that compulsory licensing encourages voluntary licensing and collaboration. So a forceful signal from countries (as a number of countries have done early in the Covid-19 outbreak) that they are ready to take non-voluntary measures when needed is important.

There is of course, no need for compulsory measures when voluntary mechanisms are in place and effective. Such as the WHO Covid-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP) and the Medicines Patent Pool. But the uptake of the voluntary IP sharing mechanism has been very limited and for vaccines not happened at all.

Limitations to compulsory licence include:

- It is a country by country, case by case, patent by patent measure which ignores the importance of providing swift legal certainty for producers that are likely to operate globally.

- Countries that grant data and market exclusivity when registering a new drug may have difficulty providing regulatory approval for products produced or imported under a compulsory licence may be a problem if no exclusivity waiver is in place;

- Compulsory licensing concerns patents and does not extend to forms of IP that may be needed such as, know-how, trade secrets, cell-lines, regulatory filings.

So how can the pandemic treaty address IP issues?

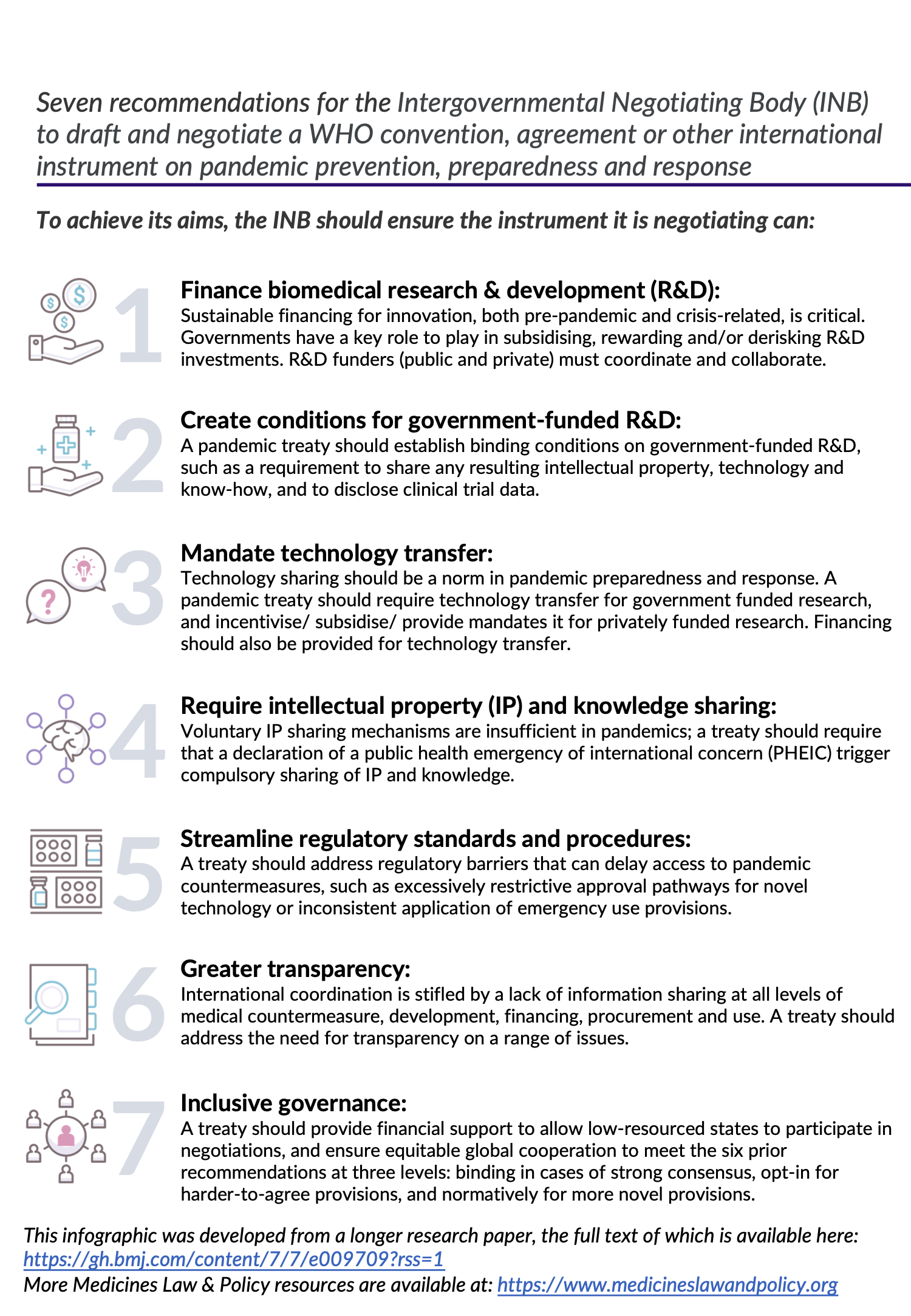

In October 2021 we held an expert working group meeting that formulated the following recommendations IP and knowledge management for pandemic preparedness and response:

Download the above infographic as a pdf by clicking here.

These measures can be agreed upon in coherence with existing international agreements on intellectual property.

The TRIPS Agreement in articles 7, 8, and 30, 31, 31bis, 44.2 and 73(b)iii offers ample scope for states to intervene in private IP rights in the public interest and to respond to a crisis and does not have to stand in the way of implementing above recommendations.

But these mechanisms may need to be applied in a coordinated manner and some of them triggered automatically through provisions in the pandemic treaty.

It may be useful to look at agreements that have dealt with limitations and exceptions to IP, such as the WIPO Treaty for the blind which created a mandatory obligation for member states to implement copyright exceptions for the creation of materials for visually impaired persons.

And agreements that dealt with technology transfer such as the Multilateral Fund (or Montreal Protocol), a successful international agreement to phase out ozone-depleting substances. The Multilateral Fund is explicitly intended to support technology transfer relating to the manufacture and use of substitutes for ozone-depleting substances.

The Pandemic Treaty offers an opportunity to coordinate the management and sharing of IP, know-how and data needed for equitable access to pandemic countermeasures. It is up to negotiators to make sure that it does so, so the world does not repeat the mistakes of Covid-19.

Kaitlin Mara, MSc, has been writing about international intellectual property and innovation policy for over 15 years.