GENEVA, SWITZERLAND: On 31 October, the World Trade Organization (WTO), the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) held their annual Trilateral Conference, entitled: “Cutting-Edge Health Technologies: Opportunities and Challenges.” At Trilateral Conferences, participants discuss issues related to intellectual property and health care.

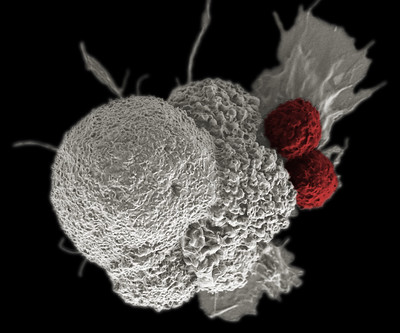

The first trilateral conference focused on the procurement of medicines for diseases affecting people in developing countries. It is a sign of the times that today the three agencies focussed on new medical technologies that create access challenges globally, including in wealthy nations. The WTO Director-General Roberto Azevêdo drew specific attention to chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy (CAR-T), a new treatment for leukaemia, a blood cancer. CAR-T uses the patient’s own T-cells that are genetically altered to attack cancer. Azevêdo said, “this is a promising area of medical research — one that involves both public and private actors. A recent survey showed that public sector research institutions held 40% of patents in this area, while private firms hold 49%. How they choose to license these technologies will be an important factor in how therapies are rolled out in practice”.

His comments are timely. There is an increasing concern about access to medical products and treatments that are developed in public and academic institutions, but once commercialised by companies become unaffordable to individuals and the health system. For example, Novartis and Gilead offer CAR-T treatment priced at US$ 373,000 (Novartis’ Yescarta) and US$ 475,000 (Gilead’s Kyriah).

CAR-T services, however, are also offered by hospitals that have the production facility for it. Such academic centres are in a position to offer the treatment at a much lower cost. According to Dr Carl June, who developed CAR-T treatment, the actual cost of producing engineered T-cells is around US$ 20,000. Physicians and patients have argued that allowing academic medical centres to make the treatment would potentially save billions. Academic institutions in several countries, including in Europe, already do so.

The EU’s Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMP) Regulation provides for a ‘hospital exemption’ which allows hospitals to make an advanced therapy available without the need to seek marketing approval through the European Medicines Agency. But how they can be protected against patent infringement suits is not yet clear.

In October of this year, Medicines Law & Policy joined Knowledge Ecology International (KEI) in organising a two-day workshop titled When drug companies become doctors at the Brocher Institute in Geneva. The workshop examined new medical technologies such as CAR-T in the context of article 27.3(a) of the TRIPS Agreement, which allows the exclusion from patentability of diagnostic, therapeutic and surgical methods for the treatment of humans or animals. One could argue that medical procedures such as gene and cell therapies, should fall under this patentability exception which may help to secure academic hospitals’ ability to offer the treatment at a lower cost. (See also our earlier report of a WIPO side event on the patentability of gene-editing therapies.)

NGOs such as KEI encourage policymakers to explore if certain cell- and gene-based treatments are, in fact, exempt from patentability when a country has an exception that mirrors Article 27.3(a) of the TRIPS Agreement. For example the European Patent Convention Article 53 (c) reads: European patents shall not be granted in respect of: (c) methods for treatment of the human or animal body by surgery or therapy and diagnostic methods practised on the human or animal body; this provision shall not apply to products, in particular substances or compositions, for use in any of these methods.

Public research institutions and academic hospitals often develop and pioneer these new medical treatments. The conditions with regards to access to and the pricing of new therapeutic knowledge when this is transferred to the commercial sector, therefore, is key.

Socially responsible licensing

In the Netherlands, upon the request of the Minister of Health, the Netherlands Federation of University Medical Centres (NFU) has formulated principles for socially responsible licensing. The guidelines stipulate that licensing of intellectual property ensure that the price-setting of the final products and services does not endanger accessibility. Specifically, the guidelines state :

A patent offers the patent holder/licence holder a legal monopoly. That can have undesirable consequences, particularly with products or services for which there is a widespread or even urgent need, like medicines and medical devices. When arranging a licence, it can therefore be agreed that the partner will endeavour to make a reasonable commercial effort to ensure that the final price of the product or service will not hinder its availability in a particular market. The criterion to determine what is acceptable depends on the context at the time that the product or service is marketed. That is more realistic than setting a price in advance, although the development can take years. Such an agreement protects against excesses, when knowledge supported by public funding leads to products that are unaffordable for the public. Likewise, there should be an agreement that this arrangement will not be undermined by the partner setting unreasonably burdensome conditions that make availability unnecessarily complex or unfeasible.

At a 5 November event organised by WEMOS and Health Action International in collaboration with the University of Utrecht, Prof Miedema (who chaired the commission that drew up the NFU guidelines) said that the next steps involve developing model clauses for research institutes to use in their agreements with the commercial sector. Enforcement of the principles contained in the guidelines remains a significant challenge. Not in the least because academic institutions seem to believe that they do not have much bargaining power when dealing with large corporations. This power balance would change if guidelines for responsible licensing were more widely adopted in Europe. But even then legislative change remains necessary because the current pharmaceutical legislation signals to industry the exact opposite of social responsibility: as far as pricing is concerned, the sky is the limit. See here for proposals on how this can be changed.

On 3 December, the French National Assembly set the first step towards legislative change. The Assembly adopted a ‘transparency amendment’ to the social security budget bill that requires drug companies to disclose public financing they have received for the development of the medical product they are seeking to market in France. The comité économique des produits de santé (CEPS), the French government body in charge of setting prices for reimbursement can take this information into consideration when negotiating drug prices. The transparency amendment was supported by the Observatoire Transparence Médicaments (OTM) a civil society drug pricing watch group. OTM called the adoption of the amendment a ‘historic advance’ in the quest for greater transparency in medicine pricing and cost. The French legislative move followed the adoption of the transparency resolution by the World Health Assembly earlier this year, which set out new norms for disclosure of drug pricing and cost.

Ellen ‘t Hoen, LLM PhD, is a lawyer and public health advocate with over 30 years of experience working on pharmaceutical and intellectual property policies.