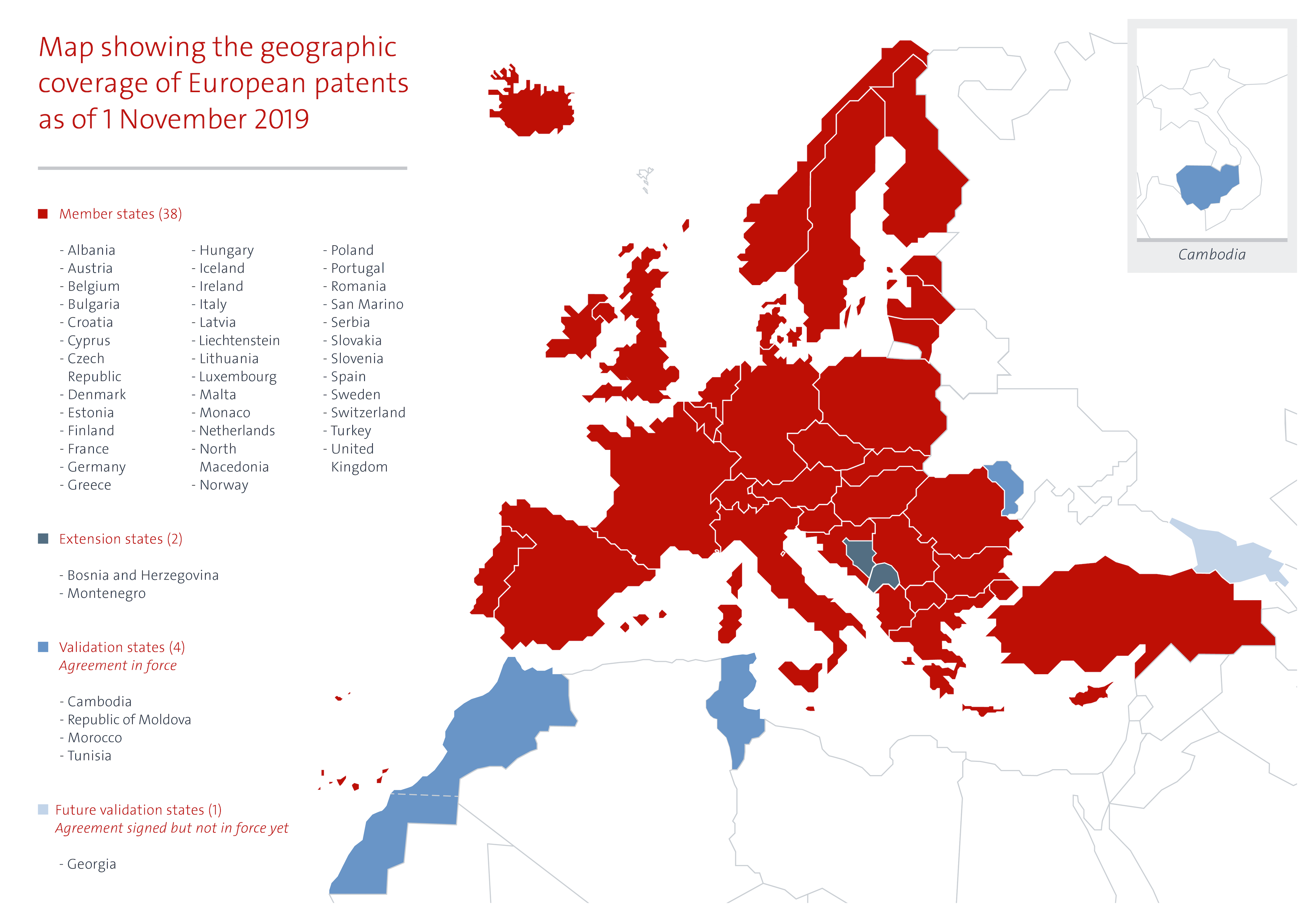

The European Patent Office (EPO) is tasked with the examination of patent applications and the granting of patents when these applications meet the patentability criteria. The European Patent Convention (EPC) which was signed in 1973, sets out the rules for the EPO’s work. In 2018, the EPO granted a total of 127625 patents and received 174317 patent applications of which 14000 were related to pharmaceuticals or biotech products. The EPO’s 2.4 billion Euro budget is entirely financed by the patent applicants who pay a fee for the examination and maintenance of the patents. Patents granted by the EPO can be valid in up to 44 countries, e.g. the 38 countries that are a member of the EPC (these include all 28 EU member states) and 2 European but non-EPC members and countries with which the EPO has signed a validation agreement.

Since 2010, the EPO has signed five validation agreements with countries that are not a member of the EPC, so-called non-contracting parties that are outside the European region. These are called “validation states”. Patent applications filed at the EPO can be automatically validated in the validation state against the payment of a fee by the patent applicant. Once the EPO publishes the mention of the grant, a European patent validated has the same effects as a national patent.

The EPO has concluded validation agreements with Morocco (2010, entered into force on 1 March 2015), Republic of Moldova (2013, entered into force on 1 November 2015), Tunisia (2014, entered into force on 1 December 2017), Cambodia (2017, entered into force on 1 March 2018) and Georgia (2018, not yet entered into force).

Further, the EPO is in talks with what it calls “candidate countries for validation” including, Angola, Laos, Jordan and the Organisation Africaine de la Propriété Intellectuelle (OAPI). The EPO claims that “Validation has proven to be a successful measure for reducing the backlog of patent applications, and releasing resources to strengthen local innovation ecosystems.” This statement ignores the fact that developing countries have great difficulty paying for the high price of patented medicines and are seeking ways to reduce this burden including by limiting the number of patents granted for pharmaceuticals.

The TRIPS Agreement offers important flexibility to countries to design a patent system conducive to their developmental and health needs. For example, in 2006 India amended its patent law so it complies with TRIPS but also put breaks on ever-greening of medicines patents by excluding new forms of known substances from patent protection unless increased efficacy can be demonstrated (Section 3(d) Indian Patents Act). In 2012 Argentina introduced new Guidelines for the Patentability Examination of Patent Application for Chemical and Pharmaceutical inventions aimed at awarding real innovations but limiting secondary patents related to already existing molecules. Also, Brazil has taken measures against ever-greening of patents by providing its medicines regulatory agency with a role in the examination process. South Africa, in 2018, formulated a national intellectual property (IP) policy that is sensitive to issues of justice and public health and the government is currently in the process of drafting new IP legislation. While South Africa collaborates with other patent offices, including the EPO, it takes decisions within the confines of its own national IP law. In 2019, Uganda notified the African Regional Intellectual Property Organisation (ARIPO) that pharmaceutical inventions are not eligible for patentability in the country. Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe also retain the right to refuse patent applications based on the grounds that they ‘claim as an invention a substance capable of being used as food or medicine’.

The diverse and country specific medicine patent policies would be difficult to maintain for countries that sign up for EPO validation agreements.

The listing of Angola and Laos, both LDCs and OAPI (out of the 17 OAPI members, 12 are LDCs) is of particular concern because LDCs are exempted from TRIPS implementation (with the exception of Articles 3, 4 and 5 of the Agreement), for as long as the LDC transition period remains in force. This transition period was last extended in 2013 to 1 July 2021. For details see here. Further, they are not obligated to grant or enforce pharmaceutical product patents, until at least 2033. Entering into a validation agreement with the EPO, without reference to the transition periods for LDCs and stipulating the exclusion of pharmaceutical product patents may lead to closing the transition window prematurely. If Laos or Angola would agree to recognise the validity of EPO patents without exceptions, it would annul one of the most powerful flexibilities available to LDCs. OAPI has amended the Bangui agreement to implement the LDC exception (although this amendment is not yet in force). See also here. For a model use of this LDC flexibility see here.

Cambodia, the first LDC to entre into a validation agreement with the EPO, has excluded pharmaceutical product patents from patentability in its national law. This is acknowledged in the agreement with the EPO as follows:

3.1 It is important to draw the attention of applicants to the fact that under the Law on Patents in force in Cambodia, pharmaceutical products are excluded from patent protection. Cambodia currently benefits from the World Trade Organisation waiver allowing Least Developed Countries (LDCs) to avoid granting and enforcing IP rights on pharmaceutical products until 2033. This waiver would also apply to European patents providing protection for pharmaceutical products, for which validation is sought in Cambodia.

3.2 Applicants can, however, benefit under Article 70.8 TRIPS of a so-called “mailbox system”. According to this “mailbox system”, Cambodian legislation authorises the filing of patent applications for pharmaceutical products, despite the fact that they are excluded from patent protection. These national applications will not be examined as to their patentability until the end of the transitional period. Following that period, protection may be granted for the remainder of the patent term, computed from the filing date of the application.

But not all LDCs have implemented such TRIPS flexibilities in their national law and doing so after entering into a validation agreement with the EPO may prove to be difficult.

The EPO’s drive to sign countries up for the validation agreement seems somewhat tone-deaf to the issue of access to medicines. Developing countries are still shaping patent policies to fit their development challenges and public health needs while meeting the requirements of the WTO TRIPS Agreement. European countries have recognised the importance of the policy space to protect public health and outlined in the Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health, and they would do well to ensure that the EPO does the same.

Ellen ‘t Hoen, LLM PhD, is a lawyer and public health advocate with over 30 years of experience working on pharmaceutical and intellectual property policies.