This article is also available as a PDF here.

Almost 26 years ago, here in Amsterdam, on November 25-26, 1999, Health Action International, Médecins Sans Frontières, and the Consumer Project on Technology collaboratively organised a conference titled “Increasing Access to Essential Drugs in a Globalised Economy: Working Towards Solutions.”

This event was groundbreaking, gathering 350 representatives from civil society, government, industry, and academic institutions from 50 countries at a time when HIV was killing 8000 people a day in the developing world. While effective HIV medications were available in affluent nations, they were priced out of reach of the 30 million people infected with HIV. Effective antiretroviral medicines had been developed, mainly with US government funding made available as a result of intense campaigning by groups such as ACT UP in the US.

Despite the death toll in the developing world, in ‘99, HIV medicines were not on the World Health Organization (WHO) Essential Medicines List, mainly because of their high price. Since 1977, the List has been WHO guidance to countries for the selection and procurement of medicines to respond to the health needs of their populations. Since HIV medications were relatively new, they were available from patent-holding companies only, who charged monopoly prices: prices unrelated to the cost of development and production. As a result, the medicines were not available in the countries where the HIV outbreak caused most illness and death.

The Amsterdam Conference focused on new ways to provide equitably priced medicines and to ensure research and development into new medicines for infectious diseases. The concluding statement from the conference pointed out that: “Market forces alone will not address this need: political action is demanded.”

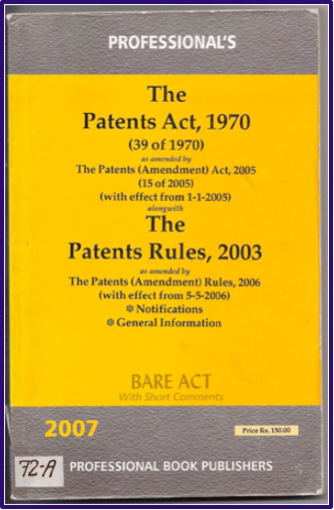

The statement made several recommendations to readjust the international trade rules that globalised intellectual property rules and had, among other things, introduced the obligation on countries to provide a minimum of 20-year patents on pharmaceuticals. These rules, contained in the World Trade Organization (WTO) Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement, came into force in 1995. The HIV crisis had begun to show the effects of patents on access to medicines. This also raised concerns for access to other new essential medicines. After all, the WHO Essential Medicines Cconcept strongly leaned on the availability of affordable generic medicines. These generic medicines were mostly produced in developing countries with production capacity. India, for example, became known as the pharmacy of the developing world. The new international intellectual property rules risked drying up these sources of affordable generic medicines when producing countries started to grant pharmaceutical product patents.

In ‘99, a delegation from the Amsterdam Conference took recommendations for rebalancing these rules to protect public health directly to the 3rd WTO Ministerial Conference in Seattle.

On October 15, 1999, Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières, MSF) received the Nobel Peace Prize. They decided to dedicate the prize money to advocating for access to essential medicines, including research and development (R&D) for neglected diseases. And this gave the organisation a strong voice and platform. The 3rd WTO Ministerial in Seattle collapsed, but civil society organisations had nevertheless succeeded in putting the issue of access to medicines on the agenda. Thanks to the fabulous MSF logistics teams who knew how to navigate in war zones, civil society representatives to the conference could move around in Seattle and visit the country delegations and put on seminars in the hotels where they were staying.

No longer able to turn a deaf ear to the chorus of critics, the WTO changed course. The Zimbabwean Chair of the WTO TRIPS Council proposed a special session of the WTO TRIPS Council on access to medicines because “the WTO can no longer ignore the issue that was being actively debated outside the WTO but not within it”.

Two years later, in 2001, when the next WTO Ministerial took place in Doha it adopted the landmark Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health, setting out the flexibilities contained in the TRIPS Agreement that countries could use to access lower-priced versions of medical products.

Trade disputes with countries that tried to access generic medicines played a very important role in the politics of all of this. For example, the ill-advised court case by multinational pharma companies vs the South African Mandela government over a TRIPS-compliant import provision in the South African medicines act. The offer of antiretrovirals (ARVs) at 1US$ a day by the Indian generic company Cipla in 2001 also demonstrated that access to HIV treatment at wide-scale was possible.

Countries started to access generic lower lower-priced antiretroviral medicines using the so-called TRIPS flexibilities referenced in the Doha declaration, often spurred on by national civil society campaigns. This did not always sit well with the high income countries, in particular those that were home to the pharmaceutical industry. For example, the predominant view of the European Commission’s Directorate General for Trade was that “health should not have primacy over intellectual property”, though the Doha declaration made clear the international consensus that the TRIPS agreement should be implemented “in a manner supportive of public health”.

The 2001 Doha Declaration saved lives, and it invigorated a civil society movement that went on to work on a number of policy issues that became tremendously important for access to essential medicines. Some key milestones in this work include:

- 2001: NGOs successfully lobbied the WHO for the establishment of WHO Prequalification, which enabled UN agencies and governments to more easily procure generic medicines. Prequalification was initially for HIV, and today covers a wide range of illnesses.

- April 2002: The requirement for affordable prices was changed for the inclusion of medicines in the WHO Essential Medicines List (EML), opening the door to the argument that a medicine deemed essential must become affordably available.

- 2001: Following intense campaigns by students, Yale University renegotiated its licence agreement with BMS for the HIV drug stavudine, allowing for patent relief and manufacture of low-cost generic versions. This sparked the global movement Universities Allied for Essential Medicines (UAEM), which is still active today.

- 2002: In South Africa, the Treatment Action Campaign and others used competition law to combat excessive pricing of ARVs, forcing the originator companies to enter into licensing agreements. One of their well known cases was known as the Hazel Tau Case.

- 2003: Funding mechanisms such as the Global Fund to Fight HIV, TB, and Malaria and the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) were established. And until this day, civil society is campaigning to protect funding for the prevention and treatment of disease.

- 2003: The Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi) was created with support from MSF and several countries. The DNDi has delivered 13 affordable new treatments, including two new chemical entities, for six deadly diseases. It also inspired the creation of other not-for-profit drug development initiatives.

- 2005: The Indian Patent Act was amended to become TRIPS-compliant, but at the same time introduced strict patentability criteria to limit patents to real innovation. A proposal for which civil society campaigned hard. Civil society went on to leverage these provisions to challenge patents, notably on imatinib (an anticancer drug), preserving generic production and inspiring other nations to use compulsory licensing to purchase Indian generic imatinib. It also introduced a simple provision for compulsory licensing for export to countries without sufficient production capacity.

- 2008: The WHO Global Strategy and Plan of Action on Intellectual Property and Public Health (GSPOA) was adopted by the WHA. This strategy focused on access to medicines and alternative R&D financing, recommending continued exploration of an essential health and biomedical R&D treaty and assessing the feasibility of a medicines patent pool (initially proposed by James Love of Knowledge Ecology International (KEI) in 2002).The GSPOA was followed by the Consultative Expert Working Group on R&D which recommended in 2012 that WHO member states start negotiations on a medical R&D treaty.

- 2010: Unitaid established the Medicines Patent Pool with support from various governments. The US National Institutes of Health was the first licensor of HIV medicine patents, a move strongly supported by the Obama White House following lobbying efforts by US treatment action campaigners. Pharmaceutical companies subsequently joined. Civil society organisations that supported the MPP were instrumental in its success.

- 2019: The WHA Transparency Resolution, a direct result of civil society proposals for greater price and R&D cost transparency at the WHO Fair Pricing Forum, was adopted.

- 2020 May: Proposed by Costa Rica, the WHO established the COVID-19 Technology Access Pool (CTAP). KEI, who had proposed the Medicines Patent Pool, was one of the fiercest supporters of the initiative.

- 2025: New essential medicines (e.g., for cystic fibrosis) were included in the WHO EML following submissions by campaigns like Right to Breathe and JustTreatment, demonstrating patient groups’ growing influence, mirroring the HIV movement.

- And this week, civil society organisations joined forces to open a buyers club for generic cystic fibrosis medicinesoffering the treatment for US$ 6375. The originator’s list price is US$ 370.000.

This overview, while acknowledging its incompleteness, demonstrates the undeniable impact of the access movement. Civil society actions have been instrumental in driving most of the significant policy developments in access to medicines over the past 25 years.

But how solid are these changes?

The Covid-19 outbreak offered us a stark reminder of how quickly international collaboration and solidarity go out of the window in a crisis. It also showed the failure to apply the lessons from previous pandemics. Very quickly, vaccine nationalism took over, the High-Income Countries (HICs) served themselves, even within the EU. There was an abundance of vaccines in the North while and developing countries, where stuck on the waiting list. Vaccine production know-how was not shared. Despite the fact that WHO had established a COVID-19 Technology Access Pool (CTAP), modelled after the MPP, to be able to ramp up production of pandemic countermeasures, companies simply refused to engage with it. Except for AstraZeneca, they also did not license their IP and know-how to developing country producers bilaterally. Governments, spending billions in public financing on innovation (a very good thing) had failed to attach access and licensing conditions to this funding (much like what happened with HIV). The decision to initiate negotiations on a Pandemic Agreement at the WHO was made to ensure better preparations and greater equity of access in the event of the next pandemic, but the outcome of the negotiations does not sufficiently alter the status quo. In particular, proposals for IP sharing and technology transfer were not welcomed by HICs. At times, it felt as if decades of international debates and norm-setting on IP and access to technology never happened.

One bright spot in the Pandemic Agreement is the duty on countries to develop policies for conditions on government funding of research and development of pandemic countermeasures, such as licensing, pricing, technology transfer and collaboration. Again, this provision is a result of strong civil society engagement.

The fight for access to medicines remains a persistent global challenge, and is fought drug- by- drug and disease- by- disease, and as recognised by the 2017 Lancet Commission on Essential Medicines: It is no longer confined to developing countries. Even progress made in combating HIV is now facing setbacks because of reduced funding for global health. There is a reluctance from companies to collaborate with the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP) which is leading to less favourable license agreements. A recent example is Gilead’s lenacapavir. Lenacapavir is a long-acting product with the potential to end the HIV pandemic, and should therefore be universally accessible. Yet, Gilead decided to license this product outside the Medicines Patent Pool, and its chosen licensees are barred from supplying to many middle-income countries, even when a government issues a compulsory licence—a restriction that would not have been present under an MPP license.

Last week, we learned at a meeting organised by MSF that Johnson & Johnson refuses to enter into procurement negotiations with the European Commission to supply a bloc of EU countries affected by multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and struggling to pay the price. The negotiations aim to reduce the price of treatments for MDR-TB, which presently are priced between 20,000 and 25,000 Euros per course.

To more fundamentally address the issue of access to affordable pharmaceutical innovations, we need to look at how these innovations are financed. Today’s innovation model – except for non-profit drug development models such as the DNDi – is almost entirely based on granting monopolies. This is achieved through the patent system, as well as through medicines regulation, which grants data and market exclusivities designed to keep generic competitors off the market. Bluntly put: governments grant monopolies and then struggle to deal with the monopoly prices that put a huge burden on the health budget. It’ is not easy to negotiate with a monopolist. Monopoly pricing leads to rationing. Depriving people of medicines they need seems such a brutal way to pay for innovation.

So how to turn this around?

- Improve the policy debates. Addressing the information imbalance and increasing transparency regarding prices and R&D costs will be essential.

- Intervene in monopolies when they are the problem. Policy makers are often captured by industry’s scare tactics rather than by the need to protect public health care financing.

- Stop providing government grants and tax breaks for R&D without attaching conditions for access. Public financing is an important lever to enhance access that is not used sufficiently.

- Create a greater diversity in the ways innovation is financed (a recommendation from the ‘99 conference). Move away from mononopies as the predominant way of financing R&D and experiment with ‘delinkage models’. L- lessons can be learnt from not-for-profit drug development.

- Explore how to ensure that savings as a result of artificial intelligence used in drug development can benefit the public (instead of private profits). Artificial intelligence will likely play a greater role in drug development and offers an opportunity to change the innovation incentive mechanisms from monopoly-based to incentives that match the real cost.

I realise that this kind of change will require international collaboration and that is not easy to achieve in today’s world, torn apart by conflict, inequities, and an increasingly powerful political right which disregards human rights and solidarity and is out to weaken the multilateral system.

Even in today’s political reality, progress can be made by forming coalitions of countries across regions to explore better ways to incentivise innovation, share those innovations and ensure access. In doing so, much can be learned from initiatives taken by civil society.

To echo one of the conclusions of the ‘99 Amsterdam conference: “Market forces alone will not address this need: political action is demanded.”

I thank you.

Ellen ‘t Hoen, LLM PhD, is a lawyer and public health advocate with over 30 years of experience working on pharmaceutical and intellectual property policies.