European Parliament legislative resolution of 13 March 2024, on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on compulsory licensing for crisis management and amending Regulation (EC) 816/2006 (COM(2023)0224 – C9-0151/2023 – 2023/0129(COD))

Download this briefing note as a PDF here.

The European Commission’s proposal for a Regulation for compulsory licensing for crisis management signifies very important progress in dealing with market monopolies that create supply and access problems in crisis situations. It fills an important void in European Union law where today only individual member states can issue a compulsory licence (CL). Without an EU-wide mechanism for CL, the EU cannot leverage the single market nor assure supply for all in the EU. The Commission’s proposal will ensure both access to patents and access to information and know-how that is not disclosed in the patent or patent application but may be needed for manufacturing. The European Parliament also recognised the need to strengthen access to know-how provisions.1

However, the European Parliament has adopted a series of amendments to the Commission’s proposal that significantly weaken the text to the point that the instrument becomes unsuitable for swift response in crisis situations and, in certain situations, may even be impossible to use. This note discusses some of the most problematic provisions proposed by the European Parliament that need to be rolled back to ensure that the citizens of Europe are adequately protected during crisis situations, such as pandemics.

1. Provisions that may seriously hamper the effective use of the Regulation:

The requirement that all IP rights, rights-holders and potential licensees need to be identified

Several EP amendments introduce provisions that go above and beyond what the World Trade Organization’s Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement requires (this is also called “TRIPS-Plus”), which can hamper the effective use of the Regulation in crisis situations. This note will not address them all in detail, but the new provisions requiring that all IP rights, rights holders and potential licensees need to be identified is particularly problematic and needs to be addressed for the Regulation to be able to meet its objective.

The text as amended by the EP (see Box 1), requires that the Commission:

- Identify in its decision the patent, patent application, supplementary protection certificate and utility model related to the crisis-relevant products, and the rights-holders of those intellectual property rights as well as potential licensees, before granting the compulsory licence.

- Where the rights-holder or not all the rights-holders could be identified in a reasonable period of time, the Commission should not grant the Union compulsory licence.

Why is this problematic?

The Regulation is meant for use in crisis situations that likely require swift action. In practice, it may not always be possible to identify all rights and rights-holders in a short time frame. Therefore, the Commission’s original text to “make best efforts” to identify all rights holders by the time the CL is announced is much more realistic and suitable in a crisis or emergency situation. (see Box 2).

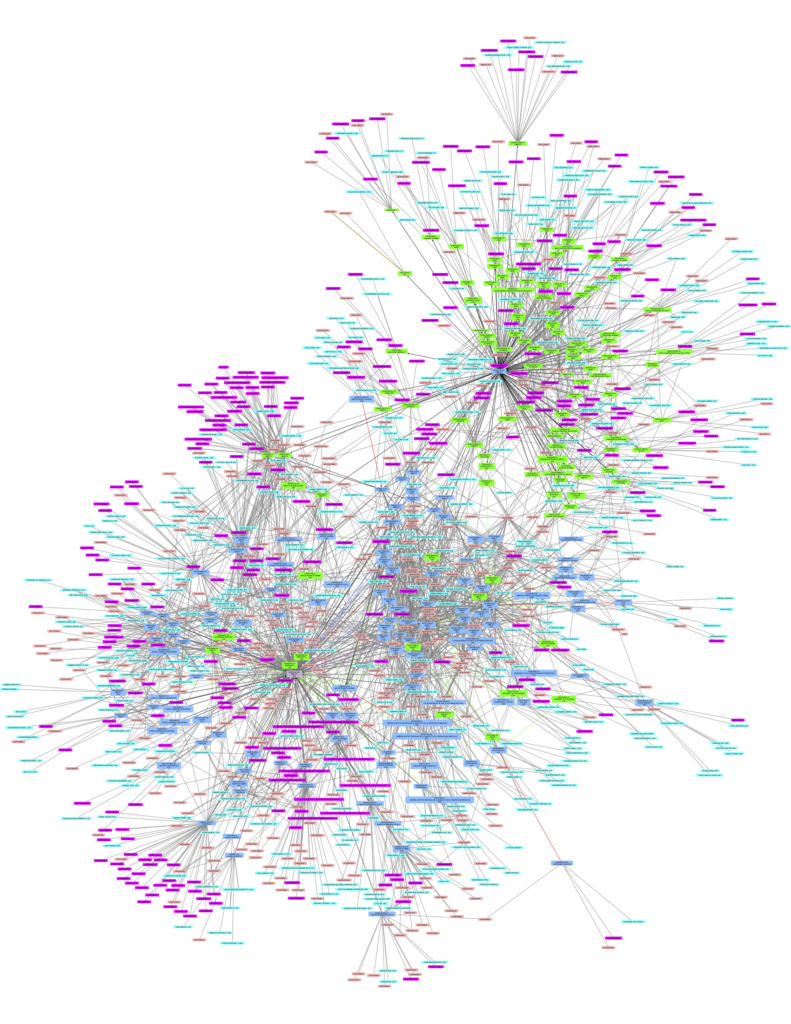

The amended text prohibits the Commission from issuing a CL if not all right holders are identified. Not only must each right-holder of a patent, patent application and supplementary protection certificate in any EU country be identified, the amendment would also require full and accurate identification of each and every patent related to the relevant product. Many complex biopharmaceutical products have a multitude of product, process, and method-of-use patents some of which have no identifying reference to the ultimate product itself (see Figure 1). Additionally, the requirement to identify all rights and rights-holders creates a “Catch-22” situation. The Commission can and likely will carry out a patent status investigation but how can one be sure not to have missed a patent-holder?

Similarly, products may be produced under licence from other patent holders and/or there may be contested claims to patent ownership or priority. Accordingly, this provision will likely paralyse the use of the Regulation because, as the Commission itself has pointed out: “a complete identification of all intellectual property rights and of their rights-holders may seriously undermine the efficient use of the Union compulsory licence to swiftly tackle the crisis or the emergency.” The Commission’s text states to publicise “where the identification of those rights would significantly delay the granting of the licence, the non-proprietary name of the products which are to be manufactured under the licence”. The International non-proprietary name (INN) is an internationally recognised name of a pharmaceutical product assigned by the World Health Organization. Publicising the INN in the announcement of the plans for a CL would help a rights-holder to self-identify and to come forward to collect royalties.

The complexity of identifying all rights and right-holders in a crisis or urgent situation is precisely why there is no such requirement in the World Trade Organization TRIPS Agreement. When a government decides to make use of a patent without the consent of the patent owner (which this regulation is about), in a crisis or urgent situation, the TRIPS Agreement requires only that: “the rights holder shall be notified as soon as reasonably practicable”. There is no TRIPS obligation to identify all rights or rights-holders prior to the grant of a compulsory licence in an urgent situation.

Figure 1: Citation map from the World Intellectual Property Organisation’s Patent Landscape of Ritonavir, demonstrating the complexity web of patents that can be attached to one medicine.

The amended Regulation puts the European Union at a disadvantage.

It is particularly noteworthy that United States law allows the government and its contractors to use patents without any advance notice to patent holders (28 U.S.C. sec. 1498). Indeed, in the US the use of patents by the government can be and has been authorised contractually merely by reference to the relevant legal authority. This is done without any prior patent search or any duty to undertake post-grant searches. Instead, the onus is on the affected US patent holder to discover the alleged government-use on its own and to thereafter seek remuneration from the government instead of the licensee. This US government-use mechanism was used dozens of times during the Covid-19 outbreak to encourage quick manufacturing and to insulate its suppliers from infringement claims. For details see: https://www.keionline.org/37987. The EP’s amendments, if maintained, are in stark contrast with US law and practice with no advantages for the EU population.

The amended text also requires the Commission to identify potential licensees at the moment the initiative to a CL is taken. In reality a licensee may not be known at the time the Commission initiates the process for issuing a CL. One could imagine an approach by which the Commission issues a CL and calls for the expression of interests from potential licensees. Such an approach will not be possible under the amended text.

Box 1. Amended Recitals 23, 24 and 25

(23) The initiation of any compulsory licensing procedure should first involve the identification of the intellectual property rights concerned, the rights-holders concerned, as well as potential licensees, with the involvement of the national authorities responsible for issuing compulsory licenses under their national patent laws. It should be publicised by means of a notice published in the Official Journal of the European Union

(24) The Commission should, assisted by the advisory body, identify in its decision the patent, patent application, supplementary protection certificate and utility model related to the crisis-relevant products, and the rights-holders of those intellectual property rights. In certain circumstances, the identification of intellectual property rights and of their respective rights-holders may require lengthy and complex investigations. The Commission should identify all applicable and relevant intellectual property rights and their rights-holder before granting the compulsory licence. The implementing act should identify any necessary safeguards and remuneration to be paid to each identified rights-holder.

(25) Where the rights-holder or not all the rights-holders could be identified in a reasonable period of time, the Commission should not grant the Union compulsory licence.

How can this be resolved?

We propose to revert back to the text of the Commission’s original proposal “to make best efforts” to identify rights and rights-holders but not let failure to do so prevent the Commission from proceeding with issuing the CL (see Box 2).

Box 2. The Commission’s original text for Recital 24

(24) The Commission should, assisted by the advisory body, make its best efforts to identify in its decision the patent, patent application, supplementary protection certificate and utility model related to the crisis-relevant products, and the rights-holders of those intellectual property rights. In certain circumstances, the identification of intellectual property rights and of their respective rights-holders may require lengthy and complex investigations. In such cases, a complete identification of all intellectual property rights and of their rights-holders may seriously undermine the efficient use of the Union compulsory licence to swiftly tackle the crisis or the emergency. Therefore, where the identification of all those intellectual property rights or rights-holders would significantly delay the granting of the Union compulsory licence, the Commission should be able to initially only indicate in the licence the non-proprietary name of the product for which it is sought. The Commission should nevertheless identify all applicable and relevant intellectual property rights and their rights-holder as soon as possible and amend the implementing act accordingly. The amended implementing act should also identify any necessary safeguards and remuneration to be paid to each identified rights-holder.

In addition, Article 7.5 that provides that the Commission publishes a notice to inform the public about its intent to issue a compulsory licence should be the beginning of the process. (See Box 3.) This notice should mark the beginning of the CL process and be published at the same time as the advisory body is consulted. Such a public notice would prompt both relevant rights-holders and potential licensees to self-identify, which allows the rights-holder to propose a voluntary agreement. In case no voluntary agreement with a view to ensuring the supply of crisis-relevant products has been reached between right-holder and the potential licensee(s) within four weeks, the procedure for granting the compulsory licence under Articles 6 and 7 would be triggered.

This approach also recognises the fact that licensees may not have been identified yet at the start of the process but will ensure they are invited to respond. In the absence of a VL, the CL should be issued no later than four weeks after the publication of the notice.

Box 3. Text of Article 7.5

When the Commission considers the granting of a Union compulsory licence, it shall without undue delay publish a notice to inform the public about the initiation of the procedure under this article. This notice shall also include, where already available and relevant, information on the subject of the compulsory licence and an invitation to submit comments in accordance with paragraph 3. The notice shall be published in the Official Journal of the European Union.

2. Compulsory Licensing is an essential tool, not a “last resort tool”

Many of the European Parliament’s amendments introduce a characterisation of the compulsory licensing instrument based on opinion rather than legal text. For Example, Recitals 16 and 40 assert that compulsory licensing is a “last resort tool,” as does Article 1.1.

This is not consistent with international law on compulsory licensing. The TRIPS Agreement and the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health contain no such limitation on the use of compulsory licensing. On the contrary, it leaves governments free to use CL and, in crisis situations, waives certain requirements, such as the obligation first to seek a voluntary licence (TRIPS Article 31 (b) ) to allow for swift use in situations of “national emergency or other circumstances of extreme urgency.” TRIPS also waives the requirement to seek a voluntary license in case of “public non-commercial use” also known as Government or Crown use. Reading the Doha Declaration makes it clear that compulsory licensing was never meant to be “a last resort tool” but instead is as a tool to promote access to medicines for all (see Box 4).

The Doha Declaration further stipulates in paragraph 5 (b) that “Each Member has the right to grant compulsory licences and the freedom to determine the grounds upon which such licences are granted”.

Box 4. Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health, Paragraph 4

We agree that the TRIPS Agreement does not and should not prevent Members from taking measures to protect public health. Accordingly, while reiterating our commitment to the TRIPS Agreement, we affirm that the Agreement can and should be interpreted and implemented in a manner supportive of WTO Members’ right to protect public health and, in particular, to promote access to medicines for all.

In this connection, we reaffirm the right of WTO Members to use, to the full, the provisions in the TRIPS Agreement, which provide flexibility for this purpose.

Nowhere does the TRIPS Agreement or subsequent WTO Declarations and Decisions restrict CL to ‘last resort’ only. It is familiar rhetoric by the pharmaceutical industry but does not find a basis in law.2 The TRIPS Flexibilities Database, which documents the use of compulsory licensing since 2001, provides further evidence that the measure is used in a variety of circumstances, including the use of patents by governments in medicines procurement.3

Another example of such rhetoric is the statement in Recital 22 that “… voluntary agreements are the most suitable way to deal with patented products or processes in a time of crisis.”

Crisis situations often require swift action, and voluntary agreements require time to negotiate, which is why they are less suitable in times of crisis. This is particularly true in the case of complex biopharmaceutical products where multiple entities might hold product, process, and method-of-use patents on final products and their components. The WTO TRIPS Agreement recognises this, and therefore, TRIPS Article 31 (b) waives the obligation to make efforts to obtain a voluntary licence in the case of “national emergency or circumstances of extreme urgency” and in the case the government makes use of a patent (“public non-commercial use”).

Moreover, the experience during the Covid-19 pandemic showed that most pharmaceutical companies routinely refused to voluntarily license vaccine patents and manufacturing know-how, even when production fell short of the global need. This provides further evidence of the untruthfulness of the statement that voluntary licensing is “the most suitable way.” Even when voluntary licences were made available, they typically excluded upper-middle-income and high-income countries.

The TRIPS Agreement specifically waives the requirement to first seek a voluntary licence “in the case of a national emergency or other circumstances of extreme urgency or in cases of public non-commercial use”. Instead, TRIPS Article 31 (b) only requires that “the right-holder shall be notified as soon as reasonably practicable.”

3. The Regulation has consequences for global health

Further the regulation explicitly prohibits any export of products produced under an EU crisis compulsory licence to other countries. This prohibition is inconsistent with international law because the TRIPS Agreement allows such exports as long as they represent a non-predominant portion (49%) of the production.

Additionally, prohibiting exports in the CL regulation would be inconsistent with the EU’s other internal market regulation (specifically the Trade Diversion Regulation 2016/793) that, like the CL regulation, concerns access to medicines and the EU’s common commercial policy.4 The Trade Diversion Regulation seeks to stimulate the private sector to export selected medicines because EU lawmakers have recognised that:

Many of the poorest developing countries are in urgent need of access to affordable essential medicines for the treatment of communicable diseases. Those countries are heavily dependent on imports of medicines as local manufacturing is scarce.5

There are both legal and practical reasons for permitting exports in the CL regulation. The legal reason is that the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU requires that the common commercial policy, and in particular, aspects of intellectual property, are conducted in the context of the principles and objectives of the EU’s external relations.6 This means that the CL regulation should take account of principles such as “the universality and indivisibility of human rights and fundamental freedoms, respect for human dignity, the principles of equality and solidarity, and respect for the principles of the United Nations Charter and international law.”7

The practical reason for permitting exports under the CL regulation is that in times of crisis, international solidarity is crucial. This was lacking during the Covid-19 outbreak, when nationalism took hold of procurement and production practices. The Regulation, as it stands, is a missed opportunity to show that the EU is committed to solidarity with other countries in times of crisis. It would be important to allow export of products produced under a CL in the European Union when such products are needed in countries outside the EU.8

The regulation as amended, which represents a restrictive implementation of an important TRIPS flexibility to ensure access to medicines, should not become the basis for promoting similar approaches in other countries. This risk is not illusionary considering that DG-TRADE policy9 is to seek, through trade agreements, similar levels of IP protection in the national law of trading partners as is provided in European Union law.

The EU Regulation for CL for crisis management should allow export of the non-predominant part of the production under a CL in a manner consistent with the TRIPS Agreement.

Endnotes

- For further information, see:

Ellen ‘t Hoen, The European Commission’s proposal for an EU wide compulsory licensing mechanism, available here: https://medicineslawandpolicy.org/2023/04/the-european-commissions-proposal-for-an-eu-wide-compulsory-licensing-mechanism/

Christopher Garrison, The European Parliament has now explicitly acknowledged the know-how problem too: time to include a workable solution in the draft Pandemic Accord, available here: https://medicineslawandpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/The-European-Parliament-has-now-explicitly-acknowledged-the-know-how-problem-too-time-to-include-a-workable-solution-in-the-draft-Pandemic-Accord.-.pdf ↩︎ - Margo A Bagley, The Morality of Compulsory Licensing as an Access to Medicines Tool, available here: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1019&context=faculty-articles ↩︎

- See also: ‘t Hoen E, Veraldi J, Toebes B, Hogerzeil HV. Medicine procurement and the use of flexibilities in the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, 2001–2016. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2018 Mar 1;96(3):185: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5840629/ ↩︎

- Note: Both the proposed CL Regulation and the Trade Diversion Regulation share a legal basis in Article 207 TFEU concerning the common commercial policy. ↩︎

- Recital 2 of Trade Diversion Regulation ↩︎

- Article 207(1), Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) ↩︎

- This comes from a list of the principles that should guide the EU’s external action, as established in Article 21(1), Treaty of the European Union. ↩︎

- See also: Olga Gurgula, The new EU compulsory licensing regime needs to allow the export of medicines, available here: https://medicineslawandpolicy.org/2023/11/the-new-eu-compulsory-licensing-regime-needs-to-allow-the-export-of-medicines/ ↩︎

- https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/enforcement-and-protection/protecting-eu-creations-inventions-and-designs_en ↩︎

Medicines Law & Policy brings together legal and policy experts in the field of access to medicines, international law, and public health. We provide policy and legal analysis, best practice models and other information that can be used by governments, non-governmental organisations, product development initiatives, funding agencies, UN agencies and others working to ensure the availability of effective, safe and affordable medicines for all.